The Un-Victim Amitava Kumar interviews Arundhati Roy, February 2011In the wake of sedition threats by the Indian government, Arundhati Roy describes the stupidest question she gets asked, the cuss-word that made her respect the power of language, and the limits of preaching nonviolence.

We

Have to be

Very

Careful

These Days

Because...

That is what I read on the little green, blue, and yellow stickers on the front door of Arundhati Roy’s home in south Delhi. Earlier in the evening I had received a message from Roy asking me to text her before my arrival so that she’d know that the person at her door wasn’t from Times Now. Times Now is a TV channel in India that Roy memorably described, for non-Indian readers, as “Fox News on acid.” The channel’s rabidly right-wing anchor routinely calls Roy “provocative” and “anti-national.” Last year, when a mob vandalized the house in which Roy was then living, the media vans, including one from Times Now, were parked outside long before the attack began. No one had informed the police. To be fair, Times Now wasn’t the only channel whose OB Van was parked in front of Roy’s house. But that too is a part of the larger point Roy has been making. Media outlets are not only complicit with the state, they are also indistinguishable from each other. The main anchor of a TV channel writes a column for a newspaper, the news editor has a talk show, etc. Roy told me that the monopoly of the media is like watching “an endless cocktail party where people are carrying their drinks from one room to the next.”

In most other homes in rich localities of Delhi those stickers on the door could be taken as apology for the heavy locks. But in Roy’s case the words assume another meaning. They mock the ways in which people rationalize their passivity and silence. You can shut your eyes, complacently turn your back on injustice, acquiesce in a crime simply by saying, “We have to be very careful these days…”

In November 2010, following a public speech she had made on the freedom struggle in Kashmir, a case of sedition was threatened against Roy. Several prominent members of the educated middle class in India spoke up on Roy’s behalf but a sizable section of this liberal set made it clear that their support of Roy was a support for the right to free speech, not for her views. What is it about Roy that so irks the Indian middle-class and elite? Is it the fact that she has no truck with the sober, scholarly, Brahmanical discourse of the respectable middle-of-the-road protectors of the status-quo? Her critics, among whom are some of my friends, are also serious people. But their objections appear hollow to me because they have never courted unpopularity. They air their opinions in op-eds, dine at the corporate table, are fêted on national TV, and collect followers on Twitter. They don’t have to face court orders. Naturally, I wanted to ask Roy whether she feels estranged from the people around her. She does, but also not. Her point is, which people? A bit melodramatically, I asked, “Are you lonely?” Roy’s wonderfully self-confident response: “If I were lonely, I’d be doing something else. But I’m not. I deploy my writing from the heart of the crowd.”

When I sat down for dinner with her I noticed the pile of papers on the far end of the wooden table. These were legal charges filed against Roy because of her statements against Indian state atrocities. Roy said to me, “These are our paper napkins these days.” What toll had these trials taken on her writing? Was her activism a source of a new political imagining or was her political experience one of loneliness and exile in her own land? What would be the shape of any new fiction she would write? These and other questions were on my mind when I began an exchange with Roy by email and then met with her twice at her home in Delhi in mid-January.

—Amitava Kumar for Guernica

Guernica: Before we begin, can you give me an example of a stupid question you are asked at interviews?

Arundhati Roy: It is difficult to answer extremely stupid questions. Very, very, difficult. Stupidity defeats you in some way. Especially when time is at a premium. And sometimes these questions are themselves mischievous.

My father turned out to be an absolutely charming, unemployed, broke, irreverent alcoholic. Guernica: Give me an example.

Arundhati Roy: “The Maoists are blowing up schools and killing children. Do you approve? Is it right to kill children?” Where do you start?

Guernica: Yes.

Arundhati Roy: There was a Hardtalk once, I believe, between some BBC guy obviously, and a Palestinian activist. He was asking questions like this—“Do you believe in killing children?”—and any question he asked, the Palestinian just said, “Ariel Sharon is a war criminal.” Once, I was on The Charlie Rose Show. Well, I was invited to be on The Charlie Rose Show. He said, “Tell me, Arundhati Roy, do you believe that India should have nuclear weapons?” So I said, “I don’t think India should have nuclear weapons. I don’t think Israel should have nuclear weapons. I don’t think the United States should have nuclear weapons.” “No, I asked you do you believe that India should have nuclear weapons.” I answered exactly the same thing. About four times… They never aired it!

Guernica: How old were you when you first became aware of the power of words?

Arundhati Roy: Pretty old I think. Maybe two. I heard about it from my disappeared father whom I met for the first time when I was about twenty-four or twenty-five years old. He turned out to be an absolutely charming, unemployed, broke, irreverent alcoholic. (After being unnerved initially, I grew very fond of him and gave thanks that he wasn’t some senior bureaucrat or golf-playing CEO.) Anyway, the first thing he asked me was, “Do you still use bad language?” I had no idea what he meant, given that the last time he saw me I was about two years old. Then he told me that on the tea estates in Assam where he worked, one day he accidentally burned me with his cigarette and that I glared at him and said “chootiya” (cunt, or imbecile)—language I’d obviously picked up in the tea-pickers’ labor quarters where I must have been shunted off to while my parents fought. My first piece of writing was when I was five… I still have those notebooks. Miss Mitten, a terrifying Australian missionary, was my teacher. She would tell me on a daily basis that she could see Satan in my eyes. In my two-sentence essay (which made it into The God of Small Things) I said, “I hate Miss Mitten, whenever I see her I see rags. I think her knickers are torn.” She’s dead now, God rest her soul. I don’t know whether these stories I’m telling you are about becoming aware of the power of words, or about developing an affection for words… the awareness of a child’s pleasure which extended beyond food and drink.

What’s interesting is trying to walk the path between honing language to make it as private as possible, then looking around, seeing what’s happening to millions, and deploying that private language to speak from the heart of a crowd.

Guernica: How has that early view changed or become refined in specific ways in the years since?

Arundhati Roy: I’m not sure that what I had then was a “view” about language—I’m not sure that I have one even now. As I said, it was just the beginnings of the recognition of pleasure. To be able to express yourself, to be able to close the gap—inasmuch as it is possible—between thought and expression is just such a relief. It’s like having the ability to draw or paint what you see, the way you see it. Behind the speed and confidence of a beautiful line in a line drawing there’s years of—usually—discipline, obsession, practice that builds on a foundation of natural talent or inclination of course. It’s like sport. A sentence can be like that. Language is like that. It takes a while to become yours, to listen to you, to obey you, and for you to obey it. I have a clear memory of language swimming towards me. Of my willing it out of the water. Of it being blurred, inaccessible, inchoate… and then of it emerging. Sharply outlined, custom-made.

Guernica: As far as writing is concerned, do you have models, especially those that have remained so for a long time?

Arundhati Roy: Do I have models? Maybe I wouldn’t use that word because it sounds like there are people who I admire so much that I would like to become them, or to be like them… I don’t feel that about anybody. But if you mean are there writers I love and admire—yes of course there are. So many. But that would be a whole new interview wouldn’t it? Apart from Shakespeare, James Joyce, and Nabokov, Neruda, Eduardo Galeano, John Berger, right now I’m becoming fascinated by Urdu poets who I am ashamed to say I know so little about… But I’m learning. I’m reading Hafiz. There are so many wonderful writers, my ancestors that have lived in the world. I cannot begin to list them. However, it isn’t only writers who inspire my idea of storytelling. Look at the Kathakali dancer, the ease with which he can shift gears within a story—from humor to epiphany, from bestiality to tenderness, from the epic to the intimate—that ability, that range, is what I really admire. To me it’s that ease—it’s a kind of athleticism—like watching a beautiful, easy runner—a cheetah on the move—that is proof of the fitness of the storyteller.

Guernica: American readers got their introduction to you when, a bit before The God of Small Things was published, an excerpt appeared in the New Yorker issue on India. There was a photograph there of you with other Indian writers, including Rushdie, Amitav Ghosh, Vikram Seth, Vikram Chandra, Anita Desai, Kiran Desai, and a few others. In the time since then, your trajectory as a writer has defined very sharply your difference from everyone in that group. Did you even ever want to belong in it?

Arundhati Roy: I chuckle when I remember that day. I think everybody was being a bit spiky with everybody else. There were muted arguments, sulks, and mutterings. There was brittle politeness. Everybody was a little uncomfortable, wondering what exactly it was that we had in common, what qualified us to be herded into the same photograph? And yet it was for The New Yorker, and who didn’t want to be in The New Yorker? It was the fiftieth anniversary of India’s Independence and this particular issue was meant to be about the renaissance of Indian-English writing. But when we went for lunch afterward the bus that had been booked to take us was almost empty—it turned out that there weren’t many of us, after all. And who were we anyway? Indian writers? But the great majority of the people in our own country neither knew nor cared very much about who we were or what we wrote. Anyway, I don’t think anybody in that photograph felt they really belonged in the same “group” as the next person. Isn’t that what writers are? Great individualists? I don’t lose sleep about my differences or similarities with other writers. For me, what’s more interesting is trying to walk the path between the act of honing language to make it as private and as individual as possible, and then looking around, seeing what’s happening to millions of people and deploying that private language to speak from the heart of a crowd. Holding those two very contradictory things down is a fascinating enterprise. I am a part of a great deal of frenetic political activity here. I’ve spent the last six months traveling across the country, speaking at huge meetings in smaller towns—Ranchi, Jullundur, Bhubaneshwar, Jaipur, Srinagar—at public meetings with massive audiences, three and four thousand people—students, farmers, laborers, activists. I speak mostly in Hindi, which isn’t my language (even that has to be translated depending on where the meeting is being held). Though I write in English, my writing is immediately translated into Hindi, Telugu, Kannada, Tamil, Bengali, Malayalam, Odia. I don’t think I’m considered an “Indo-Anglian” writer any more. I seem to be drifting away from the English speaking world at high speed. My English must be changing. The way I think about language certainly is.

Guernica: We are going to entertain the fantasy that you have the time to read and write these days. What have you been reading this past year, for instance?

Arundhati Roy: I have for some reason been reading about Russia, post-revolution Russia. A stunning collection of short stories by Varlam Shalamov called Kolyma Tales. The Trial of Trotsky in Mexico. Emma Goldman’s autobiography, Living My Life. Journey Into the Whirlwind by Eugenia Ginzburg… troubling stuff. The Chinese writer Yu Hua…

Finding out about things, figuring out the real story—what you call research—is part of life for some of us. Mostly just to get over the indignity of living in a pool of propaganda, of being lied to all the time.Guernica: And writing? You have been effective, at crucial moments, as a writer-activist who introduces a strong opinion or protest when faced with an urgent issue. Often, these pieces, which are pretty lengthy, must require a lot of research—so much information sometimes sneaked into a stunning one-liner! How do you go about doing your research?

Arundhati Roy: Each of these pieces I have written over the last ten years are pieces I never wanted to write. And each time I wrote one, I thought it would be my last… Each time I write something I promise myself I’ll never do it again, because the fallout goes on for months; it takes so much of my time. Sometimes, increasingly, like of late, it turns dangerous. I actually don’t do research to write the pieces. My research isn’t project-driven. It’s the other way around—I write because the things I come to learn of from the reading and traveling I do and the stories I hear make me furious. I find out more, I cross-check, I read up, and by then I’m so shocked that I have to write. The essays I wrote on the December 13 Parliament attack are a good example—of course I had been following the case closely. I was on the Committee for the Free and Fair trial for S.A.R Geelani. Eventually he was acquitted and Mohammed Afzal was sentenced to death. I went off to Goa one monsoon, by myself with all the court papers for company. For no reason other than curiosity. I sat alone in a restaurant day after day, the only person there, while it poured and poured. I could hardly believe what I was reading. The Supreme Court judgment that said that though it didn’t have proof that Afzal was a member of a terrorist group, and the evidence against him was only circumstantial, it was sentencing him to death to “satisfy the collective conscience of society.” Just like that—in black and white. Even still, I didn’t write anything. I had promised myself “no more essays.”

But a few months later the date for the hanging was fixed. The newspapers were full of glee, talking about where the rope would come from, who the hangman would be. I knew the whole thing was a farce. I realized that if I said nothing and they went ahead and hanged him, I’d never forgive myself. So I wrote, “And his life should become extinct.” I was one of a handful of people who protested. Afzal’s still alive. It may not be because of us, it may be because his clemency petition is still pending, but I think between us we cracked the hideous consensus that had built up in the country around that case. Now at least in some quarters there is a healthy suspicion about unsubstantiated allegations in newspapers whenever they pick up people—mostly Muslims, of course—and call them “terrorists.” We can take a bit of credit for that. Now of course with the sensational confession of Swami Aseemanand in which he says the RSS [Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh] was behind the bomb blasts in Ajmer Sharif and Malegaon, and was responsible for the bombing of the Samjhauta Express—the idea of radical Hindutva groups being involved in false-flag attacks—is common knowledge.

To answer your question, I don’t really do research in order to write. Finding out about things, figuring out the real story—what you call research—is part of life now for some of us. Mostly just to get over the indignity of living in a pool of propaganda, of being lied to all the time, if nothing else.

The Indian elite has seceded into outer space. It seems to have lost the ability to understand those who have been left behind on earth.Guernica: What would it mean for you to write fiction now?

Arundhati Roy: Â It would mean finding time, carving out a little solitude, getting off the tiger. I hope it will be possible. The God of Small Things was published only a few months before the nuclear tests which ushered in a new, very frightening, and overt language of virulent nationalism. In response I wrote “The End of Imagination” which set me on a political journey which I never expected to embark on. All these years later, after writing about big dams, privatization, the wars on Iraq and Afghanistan, the Parliament attack, the occupation of Kashmir, the Maoists, and the corporatization of everything—writing which involved facing down an incredibly hostile, abusive, and dangerous middle class—the Radia tapes exposé has come like an MRI confirming a diagnosis some of us made years ago. Now it’s street talk, so I feel it’s alright for me to do something else now. It happens all the time. You say something and it sounds extreme and outrageous, and a few years down the line it’s pretty much accepted as the norm. I feel we are headed for very bad times. This is going to become a more violent place, this country. But now that it’s upon us, as a writer I’ll have to find a way to live, to witness, to communicate what’s going on. The Indian elite has seceded into outer space. It seems to have lost the ability to understand those who have been left behind on earth.

Guernica: Yes, but what do you have to do to write new fiction?

Arundhati Roy: I don’t know. I’ll have to find a language to tell the story I want to tell. By language I don’t mean English, Hindi, Urdu, Malayalam, of course. I mean something else. A way of binding together worlds that have been ripped apart. Let’s see.

Guernica: Your novel was a huge best-seller, of course. But your nonfiction books have been very popular too. In places like New York, whenever you have spoken there is always a huge turnout of adoring fans. Your books sell well here but what I’ve been amazed by is how some of your pieces, including the one published in the immediate aftermath of the September 11 attacks, become a sensation on the Internet. Could you comment on this phenomenon. Also, is it true that the New York Times refused to publish that piece?

Arundhati Roy: As far as I know the New York Times has a policy of not publishing anything that has appeared elsewhere. And I rarely write commissioned pieces. But of course “The Algebra of Infinite Justice,” the essay I wrote after 9/11, was not published in any mainstream U.S. publication—it was unthinkable at the time. But that essay was published all over the world; in the U.S. some small radio stations read it out, all of it. And yes, it flew on the net. There’s so much to say about the internet… Wikileaks, the Facebook revolution in places like Kashmir which has completely subverted the Indian media’s propaganda of noise as well as strategic silence. The Twitter uprising in Iran. I expect the internet to become a site of conflict very soon, with attempts being made by governments and big business to own and control it, to price it out of the reach of the poor… I don’t see those attempts being successful though. India’s newest and biggest war, Operation Green Hunt, is being waged against tribal people, many of whom have never seen a bus or a train, leave alone a computer. But even there, mobile phones and YouTube are playing a part.

Guernica: Talking of the New York Times, I read your recent report from Kashmir, just after you were threatened with arrest on the slightly archaic-sounding charge of sedition.

Arundhati Roy: Yes, there was that. But I think it has blown over. It would have been a bad thing for me. But I think, on balance, it would have been worse for them. It’s ludicrous because I was only saying what millions of Kashmiris have been saying for years. Interestingly, the whole thing about charging me for sedition was not started by the Government, but by a few right-wing crazies and a few irresponsible media channels like Times Now which is a bit like Fox News on acid. Even when the Mumbai attacks happened, if you remember it was the media that began baying for war with Pakistan. This cocktail of religious fundamentalism and a crazed, irresponsible, unaccountable media is becoming a very serious problem, in India as well as Pakistan. I don’t know what the solution is. Certainly not censorship…

Guernica: Can you give a sense of what is a regular day for you, or perhaps how irregular and different one day may be from another?

Arundhati Roy: My days and nights. Actually I don’t have a regular day (or night!). It has been so for years, and has nothing to do with the sedition tamasha [spectacle]. I’m not sure how I feel about this—but that’s how it is. I move around a lot. I don’t always sleep in the same place. I live a very unsettled but not un-calm life. But sometimes I feel as though I lack a skin—something that separates me from the world I live in. That absence of skin is dangerous. It invites trouble into every part of your life. It makes what is public private and what is private public. It can sometimes become very traumatic, not just for me but for those who are close to me.

Guernica: Your stance on Kashmir and also on the struggles of the tribals has drawn the ire of the Indian middle class. Who belongs to that class and what do you think gets their goat?

Arundhati Roy: The middle class goat is very sensitive about itself and very callous about other peoples’ goats.

Guernica: Your critics say that you often see the world only in black and white.

Arundhati Roy: The thing is you have to understand, Amitava, that the people who say such things are a certain section of society who think they are the universe. It is the jitterbugging elite which considers itself the whole country. Just go outside and nobody will say that to you. Go to Orissa, go to the people who are under attack, and nobody will think that there is anything remotely controversial about what I write. You know, I keep saying this, the most successful secession movement in India is the secession of the middle and upper classes to outer space. They have their own universe, their own andolan, their own Jessica Lal, their own media, their own controversies, and they’re disconnected from everything else. For them, what I write comes like an outrage. Ki yaar yeh kyaa bol rahi hai? [What the hell is she saying?] They don’t realize that they are the ones who have painted themselves into a corner.

It would be immoral of me to preach violence unless I’m prepared to pick up arms myself. It is equally immoral for me to preach nonviolence when I’m not bearing the brunt of the attack.Guernica: You have written that “people believe that faced with extermination they have the right to fight back. By any means necessary.” The knee-jerk response to this has been: Look, she’s preaching violence.

Arundhati Roy: My question is, if you are an Adivasi living in a village in a dense forest in Chhattisgarh, and that village is surrounded by eight hundred Central Reserve Police Force who have started to burn down the houses and rape the women, what are people supposed to do? Are they supposed to go on a hunger strike? They can’t. They are already hungry, they are already starving. Are they supposed to boycott goods? They can’t because they don’t have the money to buy goods. And if they go on a fast or a dharna, who is looking, who is watching? So, my position is just that it would be immoral of me to preach violence to anybody unless I’m prepared to pick up arms myself. But I think it is equally immoral for me to preach nonviolence when I’m not bearing the brunt of the attack.

Guernica: According to Macaulay, the rationale for the introduction of English in India, as we all know, was to produce a body of clerks. We have departed from that purpose, of course, but still, in our use of the language we remain remarkably conservative. I wonder sometimes whether your style itself, exuberant and excessive, isn’t for these readers a transgression.

Arundhati Roy: I wouldn’t say that it’s all Macaulay’s fault. There is something clerky and calculating about our privileged classes. They see themselves as the State or as advisors to the State, rarely as subjects. If you read columnists and editorials, most have a very clerky, “apply-through-proper-channels” approach. As though they are a shadow cabinet. Even when they are critical of the State they are what a friend once described as “reckless at slow speed.” Â So I don’t think my transgressions as far as they are concerned has only to do with my style. It’s about everything—style, substance, politics, speed. I think it worries them that I’m not a victim and that I don’t pretend to be one. They love victims and victimology. My writing is not a plea for aid or for compassion towards the poor. We’re not asking for more NGOs or charities or foundations in which the rich can massage their egos and salve their consciences with their surplus money. The critique is structural.

Guernica: Your polemical essays often draw criticism also for their length. (We are frankly envious of the space that the print media in India is able to grant you.) You have written “We need context. Always.” Is the length at which you aspire to write and explain things a result of your search for context?

Arundhati Roy: I don’t aspire to write at any particular length. What I write could be looked at as a very long essay or a very short book. Most of the time, what I write has everything to do with timing. It’s not just what I say, but when I say it. I usually write when I know the climate is turning ugly, when no one is in a mood to listen to this version of things. I know it’s going to enrage people and yet, I know that nothing is more important at that moment than to put your foot in the door.

Guernica: But even as we raise the issue of criticism, it is also important to say that some of these critics who accuse you of hyperbole and other sins are hardly our moral exemplars. I’m thinking of someone like Vir Sanghvi. His editorial about your Kashmir speech was dismissive and filled with high contempt. We’ve discovered from the recent release of the Radia tapes that people like Sanghvi were not impartial journalists: they were errand boys for corporate politicians.

Arundhati Roy: We didn’t need the Radia tapes to discover that. And I wouldn’t waste my energy railing against those who criticize or dismiss me. It’s part of their brief. I don’t expect them to stand up and applaud.

Guernica: Having read all your published writing over the past twelve years or more, I wonder: Is there anything you have written in the past that you don’t agree with anymore, that you think you were wrong about, or perhaps something about which you have dramatically changed your mind?

Arundhati Roy: You know, ironically, I wouldn’t be unhappy to be wrong about the things I’ve said. Imagine if I suddenly realized that big dams were wonderful. I could celebrate the hundreds of dams that are being planned in the Himalayas. I could celebrate the Indo-U.S. nuclear deal. But there are things about which my views have changed—because the times have changed. Most of this has to do with strategies of resistance. The Indian State has become hard and unforgiving. What it once did in places like Kashmir, Manipur, and Nagaland, it does in mainland India. So some of the strategies we inherited from the freedom movement are a bit obsolete now.

Guernica: You have pointed out that the logic of the global war on terror is the same as the logic of terrorism, making victims of civilians. Are there specific works, particularly of fiction, that have arrived close to explaining the post 9/11 world we are living in?

Arundhati Roy: Actually I haven’t really kept up with the world of fiction, sad to say. I don’t even know who won the Booker Prize from one year to the next. But when you read Neruda’s “Standard Oil Co.” you really have to believe that while things change they remain the same.

Guernica: Your old friend Baby Bush is gone. But has Obama been any better? While we are worried about the TSA at airports, in less fortunate places U.S. drone attacks are killing more civilians than militants. Shouldn’t we be raising our voices against the role played by the U.S. terrorist-industrial complex instead of backing, as you suggest, the Iraqi resistance movement?

Arundhati Roy: I hope I didn’t say we should back the Iraqi resistance movement. I’m not sure what backing a resistance movement means—saying nice things about it? I think I meant that we should become the resistance. If people outside Iraq had actually done more than just weekend demonstrations, then the pressure on the U.S. government could have been huge. Without that, the Iraqis were left on their own in a war zone in which every kind of peaceful dissent was snuffed out. Only the monstrous could survive. And then the world was called upon to condemn them. Even here in India, there are these somewhat artificial debates about  “violent” and “non-violent” resistance—basically a critique of the Maoists’ armed struggle in the mineral-rich forests of Central India. The fact is that if everybody leaves adivasis to fight their own battles against displacement and destitution, it’s impossible to expect them to be Gandhian. However, it is open to people outside the forest, well-off and middle-class people who the media pays mind to, to become a part of the resistance. If they stood up, then perhaps those in the forest would not need to resort to arms. If they won’t stand up, then there’s not much point in their preaching morality to the victims of the war. About Bush and Obama: frankly, I’m tired of debating U.S. politics. There are new kings on the block now.

Sphere: Related Content

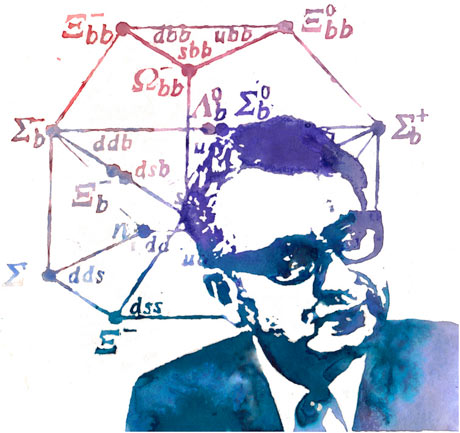

Murray Gell-Mann, captain quark, by Toyah Walker, from Lily's quarks.

Murray Gell-Mann, captain quark, by Toyah Walker, from Lily's quarks.